Perfume Dupes: Are They Taking Over?

The how, the why and the existential crises posed by fragrance copycats.

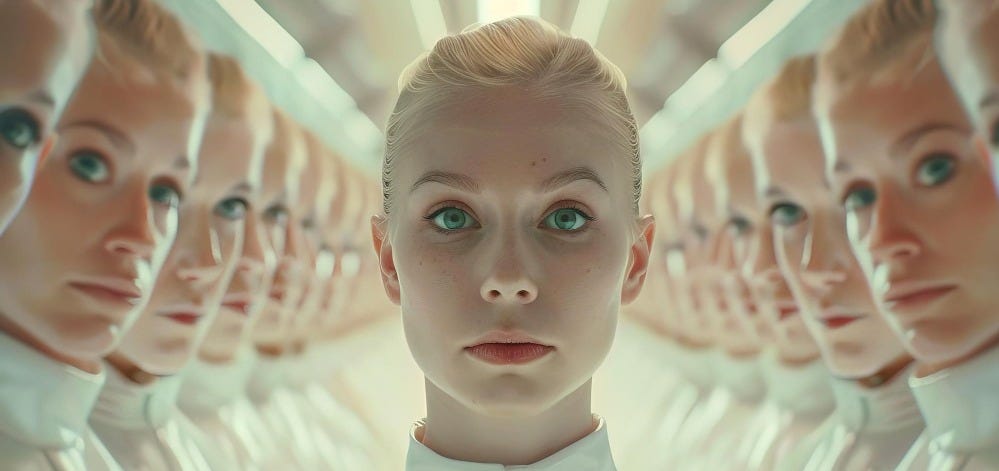

Part 1 - Rise of the Doppelgänger

Anyone familiar with the mind-numbing boredom of working in retail during quiet periods will be a dab hand at a made-up game. In 2011, when my line manager thought I was diligently checking stock or doing paperwork, I was more often passing the time with my colleagues playing such games as “Would you rather” or “Guess the song when I sing it out of tune and without any consonants”. My favourite, however, was a game of our own invention dubbed “Nur or Nur-t sure?”.

I was working in the perfumery at Fortnum & Mason and the fragrance brand SoOud had just released a scent called Nur1 that had become immensely popular. People would arrive, brandishing a photo of a simple white bottle with a lipstick-shaped lid, then leave minutes later having purchased 5-10 bottles, as coolly as if they’d popped in for some milk. It was astonishing.

In the year that followed my colleagues and I saw, for the first time, a wave of copycats arrive in Nur’s wake. From tiny brands to huge established houses, it felt like everyone was trying to cash in on SoOud’s success. Not that we cared. It simply gave us a teeming mass of perfumes to blind-smell and work out the real one, hence “Nur or Nur-t Sure?”.

Meanwhile, the likes of Santal 33 and Aventus were now picking up serious steam, which later prompted more imitations and gave us new opportunities to play our game. Even the more localised successes like Xerjoff’s Alexandria or Lorenzo Villoresi’s Teint de Neige were starting to be flanked by doppelgängers. The brands that would historically do large amounts of consumer research before creating a scent (which, in its own way, is also somewhat inauthentic) were now taking the hyper-easy route by simply imitating whatever the hype scent of the moment happened to be.

However, it wasn’t until a couple of years later that I truly started to pay attention. On a trip to Brighton with my (now) wife we stumbled upon the newly founded Eden Perfumes, a copycat shop. I’d seen outlets selling fakes before but only abroad and usually with desperately erroneous designs housing scents that were about as convincing as Clark Kent’s glasses.

This, however, was very different. This was an actual high street shop, with its own branding, a proper shop fit and, to my surprise, a takeaway-esque menu of scents that included everything from Dior to the little-known houses I worked with in Fortnum’s. The copies were most assuredly not identical, but they were pretty close.

It didn’t take long for my Uncle to become the perfect example of how many people felt. He went from happily spending hundreds of pounds on perfumes (independently of my influence) to emphatically saying “Why would I, when this is so cheap and smells practically the same?”.

Unbeknownst to him, his question had perfectly articulated the wider issue posed by the “dupe” houses developing their own identity.

I don’t imagine that Creed was quaking in its boots about the Aventus lookalikes springing up amongst its peers, because they were being pitched at a similar price and most customers reasoned, "If I’m gonna spend £200, I’ll spend it on the real thing”. Neither did it have cause to be nervous about dupe companies taking sales away from them. It was the message that was the issue.

By drastically undercutting the price these copies were also implying that, if Creed wanted to, Aventus could be sold for a lot less. And that shifted the brand position from aspirational to greedy.

Part 2: How Are Clones Made?

The Technical, The Legal and The Agent Smiths

In hindsight, dupe culture took a long time to start. The main instrument used to create them was invented in Michigan in the mid-1950s.

A GC/MS machine combines two techniques; Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. Two researchers for the Dow Chemical Company discovered that, when paired together, these techniques could give an unambiguous analysis of a vapour’s components. In essence (pun very much intended), it could tell you what a scent was made of.

Rebuilding something is much easier once you know its component parts, but it’s important to understand that it doesn't make the job entirely easy. GC/MS doesn’t provide paint-by-numbers instructions and the world of scent has infinite variables that can complicate things. For this reason, many dupe houses now purport to have in-house perfumers who can analyse the data and fill in the gaps using their knowledge and, of course, nose.

But even then, the immovable stumbling block to creating low-cost products is budget. Many perfume materials can be eye-wateringly expensive and are nigh-on impossible to imitate using cheaper alternatives. Dupes are therefore restricted in a way that many genuine brands aren’t because they have no choice but to produce them cheaply.

In addition, some perfume producers have come up with ingenious ways to stop imitators in their tracks. Franck Muller, for instance, is produced by CPL Aromas who use a proprietary technique called AromaFusion to create new, unique materials for their perfumers to use. These unique materials contain, in their words, “indistinguishable ingredients which cannot be precisely replicated”.

All in all, duping is very rarely an exact science.

Of course, these challenges haven’t stopped counterfeit producers from trying, nor do many of their customers care about 100% accuracy and so, the growth rates of dupe companies have been astronomical.

What I found unnerving at this year’s Esxence (an incredible perfume trade show in Milan, famed for its support of genuine artisanal houses) were the exhibition displays from houses that had originated as dupe producers. It was as if Agent Smith had found his way out of The Matrix and started to regenerate in new forms.

Even more unsettling, I was also told by a brand owner (who shall remain nameless) that when they spoke out about a dupe house imitating their scent on social media their accounts were swamped with spam and days later were removed by the platform.

Hang on a second though. How is all this legal? If I tried to claim Blinding Lights by The Weeknd was my song, legal teams would be on my arse faster than you can say “Mechanical License”.

Well, as it stands, there is no legal way to protect a scent. Aspects such as the name and the formulae can be protected, but an actual scent cannot. Our experience of scents is considered too subjective so it’s “discarded as a form of artistic expression”.

There was, however, a landmark case when a court ruled in favour of a claimant who decided to take on an imitator. The Dutch court (which has more lenient rules on such matters) upheld an appeal from Lancôme2 because when their original and the accused dupe were both put under chemical analysis, the result found they were the exact same.

But as we’ve established, dupes are very rarely the exact same. So whilst that particular house got a smack on the wrist, others know that a slight tweak in the formula can (theoretically) keep a counterfeit out of the courts, even if the scents are, to you and I, perceptibly the same.

And, so long as they’re careful enough to claim that the scents are “Inspired by” and not, without meaning to put too fine a point on it, “plagiarising” the original, they don’t need to worry.

You hear that, Mr Anderson? That is the sound of inevitability - Agent Smith

Part 3: Filthy Rich

I’ve always had a theory that once something reaches a certain level of success it ceases to be considered human. You see it in celebrity culture where, the bigger the celebrity, the more the media treats them as a product to exploit, rather than an actual person.

There’s a similarity in how most people will rally behind the dreams of a small business, but disassociate once it reaches a certain level. I imagine this is because of our cultural assumption that success equals money; the assumption that says “If a brand is popular, then the proprietor/s must be filthy rich.”

In some cases, that is true. Byredo was rumoured to have been acquired for $1 Billion, Creed for a staggering $3.8 Billion. When dupe houses and their customers justify the plagiarism of such monolithic brands by saying “They can afford it” they are right; they can.

The problem is that our perception also shapes our reality. So when a small business, with great products, is positioned in a prestige store next to these big guns, it’s easy to think of them as one and the same when they are absolutely not. Running a small business of any kind is fraught with difficulties that almost always come down to one thing - cash.

I balked when I first heard that a £100 perfume could cost £10 to manufacture. What a rip-off. However, what I didn’t consider at the time, was the following.

20% of that is VAT. After that, a portion went to the retailer and the rest had to go towards covering the costs of staffing, distribution and shipping, componentry, ideation, design, tooling, storage, compliance, legal, accountancy, the small bits in between like stationery or software, new product development, marketing, PR and, oh yeah, ideally pay something towards the owner/s making a living which, I soon found out, it often doesn’t.

Over time I learnt that thinking of a perfume’s markup as profit is short-sighted. Brands don’t greedily stuff our cash into their pockets and scuttle off to guffaw at our expense over their champagne and lobster dinner. Starting a genuine perfume house requires a huge financial risk, turning profits can take a very long time and most of them fail. It is, in short, really, really hard and dupes massively undermine this by reinforcing our natural (but flawed) assumption that the only cost worth our consideration is the perfume’s physical manufacture.

But back to the perfume. With such overwhelming odds, I can sympathise with brands wanting to give themselves the best chance of success by choosing to emulate a scent with a proven sales record. It doesn’t justify it (nor, in my view, does it make long-term business sense) but at least it gives some context to their decision.

I can also level with people who wish to own the original scent but feel it’s not worth the asking price, or perhaps can’t afford it. However, dig even just a tiny bit deeper and you’ll find brands like Gallivant, 100Bon, Acqua di Parma, Essential Parfums, Bon Parfumeur, and Le Jardin Retrouvé (I could go on), who all make beautiful products that, in some cases, actually cost less than a lot of dupes. A scent doesn’t have to be expensive to be good and there is still an entire world of things to enjoy on a low budget. In fact, in most cases, your budget isn’t nearly as restrictive as the temptation to settle for what is being advertised to you.

P.s. It’s easy to forget that many of those monolithic houses that people love to hate were, in fact, once small operations whose giant leap of faith happened to pay off.

Part 4: The Upsides

If you’ve made it this far you might be surprised to hear that I am, in fact, not against dupes. I’d go so far as to say that they make many hugely positive contributions to the art and industry.

A friend of mine once told me that he sometimes uses them as a way of getting to know a scent before committing to a purchase. For him, it can be a gateway into more informed decision-making, allowing him to understand where his limited budget should be spent.

Likewise, I know many people who purchased a dupe on a whim but enjoyed it so much that it led to them purchasing the real thing. Again, another gateway.

Because the anti-plagiarism laws on perfume are murky, dupes don’t have to be underhand about their work3. The fragrances can go through the proper channels to ensure safety and regulatory compliance. I’m not saying they all do (so please do your own research) but theoretically, that means fewer unchecked chemicals on the market.

Perhaps most importantly, what dupes are unwittingly doing is helping to drive awareness of the wider industry on a huge scale. I’ve spent a big chunk of my career banging on the proverbial door, trying to find ways to help bring artisan perfumery into the mainstream because, frankly, it’s really fucking cool and I wish more people cared about it. For better or worse, dupes are fighting the same fight. They are actively promoting the art of perfumery.

Ultimately, every act of buying a clone either implies that you wish to have the original or introduces you to it for the first time. By that logic, my earlier statement could be wrong. Dupes might actually serve to reinforce the aspirational element of the brand it's imitating. Perhaps imitation is not just the sincerest form of flattery, but something of a promotional support.

After all, when a dupe boasts about its accuracy to the original scent, what is it actually advertising? Yeah, the original scent.

Anyway, gotta go. I’m off to watch a tribute band.

Arabic for “Light” and created by Stephane Humbert Lucas.

This was around the same time that another legal case Lancôme was pursuing was rejected on the grounds that “perfumes are manufactured through the application of merely technical knowledge”.

There is also a school of thought that imposing anti-plagiarism rules could lead to big players monopolising the industry and creating new barriers to entry for smaller houses.